Author’s note: Immigration is a deeply important and highly emotional topic. After much contemplation, I recognized the necessity of sharing my insights with a wider audience. In a truly free society, it is essential to welcome diverse ideas and perspectives, allowing the public to decide which voices and viewpoints deserve attention. That’s why I chose to make this piece accessible to everyone, and to open the comment section for all. I urge you to read, share, and engage in the conversation, even if your views are differ from mine. This crucial issue should not be influenced by a single narrative but should reflect a multitude of voices and opinions.

President Trump’s executive orders on birthright citizenship has sparked intense debate in recent days. Supporters argue that the Fourteenth Amendment was never meant to grant citizenship to all babies born in America, while critics, including a federal judge who temporarily blocked the order, call it “unconstitutional.”

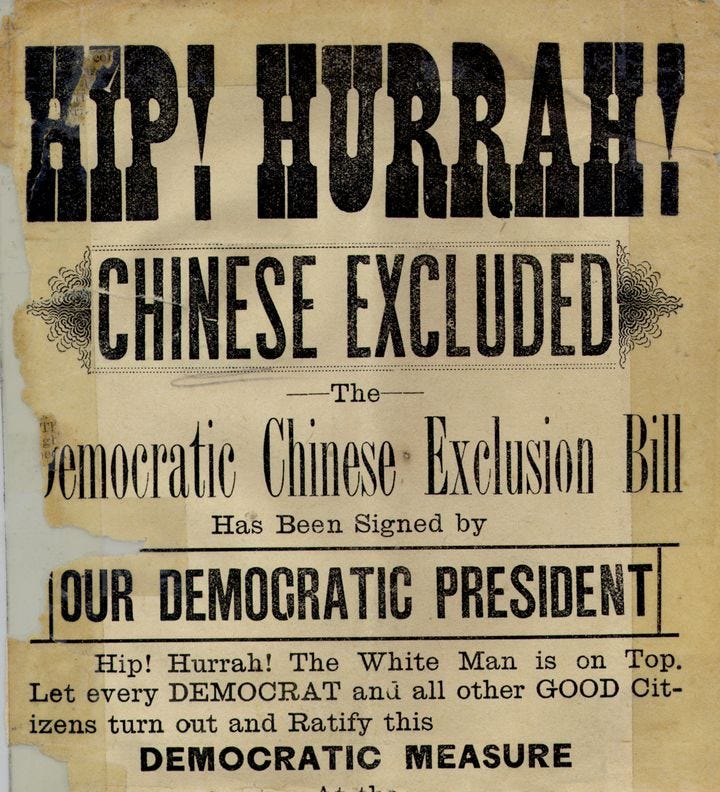

What this debate lacks is the vital perspective of Asian Americans, whose historical experiences are deeply interwoven with the concept of birthright citizenship, notably through the landmark case United States v. Wong Kim Ark. This case emerged against the backdrop of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first immigration law targeting a specific ethnic group. In the late 19th century, Chinese immigrants were subjected to blatant discrimination despite making significant contributions to America, including the construction of the transcontinental railroad and vital levees in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta region, which enabled California to reclaim thousands of acres of fertile farmland.

The discrimination faced by Chinese immigrants was frequently endorsed by the U.S. government. The most egregious instance is the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers for ten years. Those already in the U.S. were denied the right to become citizens (those who were born here fell in a grey area), and if they traveled abroad, they were required to obtain special certificates to return. This act was extended for another decade in 1892, made permanent in 1902, and not repealed until 1943.

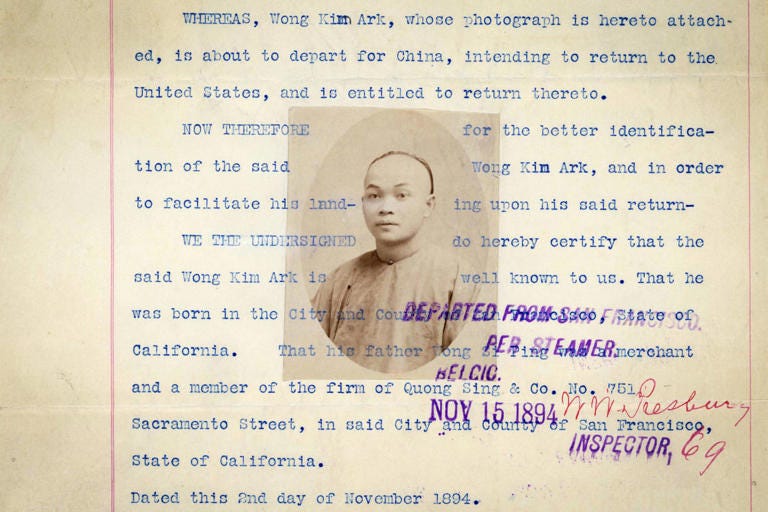

Wong Kim Ark, born in San Francisco in 1873, embodies the Chinese Americans’ struggle for justice and equality in America. Wong’s parents, immigrants from China, ran several small businesses in the city for decades. They returned to China after the Chinese exclusion Act was enacted. Wong visited them in December 1894. Upon returning in August 1895, he provided a certificate with his photograph and affidavits from prominent white citizens to confirm his U.S. citizenship.

Despite this, customs official John H. Wise decided that Wong was ineligible for birthright citizenship under the 1882 Act and detained him on a ship for deportation. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) defended Wong, filing a writ of habeas corpus to assert his birthright citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment.

U.S. District Judge William Morrow ultimately upheld Wong's citizenship, leading to his release after months of wrongful confinement. It would have been the end of the story for Wong. But the Department of Justice decided to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, aiming to use Wong’s case to deny birthright citizenship to all Chinese-born individuals.

The Supreme Court's majority decisively affirmed Wong’s birthright citizenship. The Justices concluded that Wong’s parents satisfied the "subject to the jurisdiction" requirement of the amendment because Wong’s parents "have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China, becomes at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States."

Furthermore, the court interpreted the citizenship clause through the principle of “jus soli,” establishing that birthright citizenship applies to children born in the U.S. to foreign parents, with limited exceptions, like children of foreign diplomats. Importantly, the Justices did not consider the parents’ immigration status, as the legal concept of illegal immigration did not exist at that time.

The case of The United States vs. Wong Kim Ark stands as a pivotal moment in Asian American history, marking the first time a Chinese American served as a plaintiff in the Supreme Court. Wong's victory transcended the courtroom; it became a powerful beacon of hope for the entire Chinese American community. His success demonstrated that it was possible to uphold constitutional rights and receive equitable treatment in the face of rampant racial discrimination.

In the early 20th century, following the permanent establishment of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the extension of its restrictions to other Asian immigrants, Wong inspired many others to stand up for their rights. As they followed in his footsteps, they launched legal battles against unjust immigration laws. Two notable cases—Ozawa v. United States and United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind—ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court, further solidifying the impact of Wong's landmark victory and the growing resolve of Asian Americans to fight for justice.

The impact of the United States vs. Wong Kim Ark case goes beyond Asian American communities, establishing a long-standing precedent where millions of children born in the U.S. automatically receive citizenship.

Critics of birthright citizenship, including President Trump, raise valid concerns about the exploitation of universal birthright citizenship in recent decades. One major issue is “birth tourism,” where brokers charge foreign pregnant women tens of thousands of dollars to enter the U.S. on temporary visas to give birth solely for citizenship purposes. In response, Trump proposed an executive order stating that children born to parents who entered the U.S. illegally or on temporary visas should not automatically receive citizenship. Most people with common sense will find such a proposal reasonable.

But employing an executive order to redefine a constitutional principle raises serious concerns. The framers of the Constitution entrusted the U.S. Supreme Court with the exclusive authority to interpret its language. If the executive branch can unilaterally reinterpret constitutional rights, the next Democratic administration could just as easily reinterpret the Second Amendment through similar executive actions.

Furthermore, it is concerning that the president’s executive order and his supporters, who oppose birthright citizenship, have omitted to mention the significance of the United States vs. Wong Kim Ark case, and also failed to acknowledge the history of racial discrimination against Asian Americans, especially through unjust immigration laws.

Recent infighting within the MAGA movement over the H-1B visa—a temporary work visa for skilled foreign workers—highlights how immigration debates can quickly turn into old-fashioned racism against Asians.

Many Asian Americans made a significant shift in their support from the Democratic Party to Donald Trump and the Republican Party in the last election, influencing critical battleground states like Nevada, where Trump became the first Republican presidential candidate to win since 2004. It is essential for Trump and the Republican Party to actively engage with Asian voters and not take their support for granted. As they work on shaping America’s immigration policies, I urge them to listen to a variety of voices, recognize the historical impact of immigration laws on different communities, and thoughtfully consider how these policies will define the future of our nation.

This is a wonderful article. Thanks for sharing it.

Thank you for this article. A key issue with this topic is how abused this privilege is by people who come to the United States illegally and use their U.S. born children to become part of the government entitlement programs paid for by taxpayer money.