The End of an Era

The era in which Chinese students looked forward to coming to the United States and being warmly welcomed may be coming to an end.

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio recently announced plans to “aggressively revoke” visas for Chinese students, though he did not specify when this would happen or how many would be affected. Still, his announcement marks a turning point; the era in which Chinese students looked forward to coming to the United States and being warmly welcomed may be coming to an end. This realization makes me feel sad. The presence of Chinese students in the U.S. has mostly positively impacted both China and the United States for more than 170 years. On a personal note, I was one of those Chinese students, and studying in the U.S. has profoundly changed my life for the better.

The First Chinese student

The legacy of Chinese students began with Yung Wing (容闳), who lived from 1828 to 1912. I shared his story in my new book, Not Outsiders. Brought to America by missionary Samuel Robbins Brown in 1850, Yung enrolled at Yale and quickly adapted to American culture, participating in various activities, including playing football, and graduating with the highest honors in 1854.

After returning to China, Yung persuaded the Manchu court to send more students to the United States, emphasizing the need for education to modernize China’s economy and national defense. Appointed as the head of a Chinese Education Mission, he led about 120 young students, averaging 12 years old, to study STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math) in America between 1872 and 1881.

After completing their studies, many of these Chinese students returned home and became influential leaders, transforming China by building factories, railroads, and schools that embraced Western scientific ideas. To show his gratitude for his education at Yale, Yung donated 1,237 volumes from his Chinese book collection, which formed the basis for the establishment of the East Asia Center at Yale. Yung dedicated the rest of his life to improving Sino-U.S. relations, leaving behind a remarkable legacy.

The most influential Chinese students

Following the inspiring path set by Yung, the most influential Chinese students educated in the U.S. during the first half of the 20th century hailed from the same illustrious Soong family. I shared their stories briefly in my other book, The Broken Welcome Mat.

Charlie Soong, the family patriarch, arrived in the U.S. in 1881 at the age of 18 with the help of a Southern Methodist missionary. After studying Christianity at the Trinity College (now Duke University), he return to China in 1886, and founded a Bible printing business in Shanghai, which later grew into a successful commercial empire.

Charlie also became a vital supporter and financial backer of Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary movement, which sought to overthrow the feudal Manchu government and establish a republic in China. Sun was also a Chinese student. He studied in Hawaii and was baptized by an American missionary. In 1905, Charlie made a remarkable return to the U.S., raising over $2 million from Southern Methodist church members to support Sun's revolution. In 1919, Sun's dedicated followers successfully led a rebellion in China, toppling the Manchu court and founding the Republic of China (ROC). The course of China's modern history could have been very different without generous donations from Americans.

Charlie’s four children, all educated in the United States, significantly influenced modern China. Charlie’s son, T.V. Soong, a Harvard graduate, became the finance minister and a key diplomat for the ROC. Charlie’s eldest daughter, Ai-ling, graduated from Wesleyan College and married H.H. Kong, a descendant of Confucius, who served in various ministerial roles. Ching-ling, the middle daughter and a Wesleyan alumna, was the third wife of Sun Yat-sen, earning the title “the mother of the nation.” After Sun's death, she supported the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and was appointed Vice-chairwoman when the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, making her the highest-ranking woman in the new regime.

Charlie’s youngest daughter, May-ling, started her education in the U.S. at 10 and graduated from Wellesley College in 1917. After returning to China, she married Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist Party and head of the ROC government. Her education proved invaluable during World War II, helping Chiang manage relationships with allies, especially the United States. May-ling traveled to the U.S. to raise funds for China and made history as the first Chinese person and the second woman to address a joint session of Congress.

After Chiang’s defeat in the civil war, he fled to Taiwan, where he passed away in 1975. May-ling then moved to the U.S. where she felt most at home. She passed away in New York in 2003 at the age of 106. The Soong family, all educated in America, had indisputably altered and shaped China’s modern history.

From zero to 300,000 +

After the CCP took control of mainland China, it severely restricted Chinese students’ access to education abroad. From 1949 to 1979, only a few were allowed to study in socialist nations like the former Soviet Union, while those who returned from Western studies faced persecution or even death.

Following Mao Zedong's death, the new CCP leader Deng Xiaoping recognized that China needed to send students abroad to close the widening economic and technological gap with the West. As a result, the number of mainland Chinese students in the United States surged from virtually zero to around 20,000 between 1978 and 1988. Most were state-sponsored and politically vetted, often being children of CCP officials.

After the CCP brutally cracked down the pro-democracy movement on Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, many surviving student protestors sought to escape the regime’s oppression. Pursuing advanced degrees through foreign scholarships became their best opportunity. They started a new trend among Chinese college students to find studying abroad opportunities through private means. Most Chinese students gravitated toward STEM fields in the U.S., drawn by lower language barriers, ample scholarships, and promising job prospects.

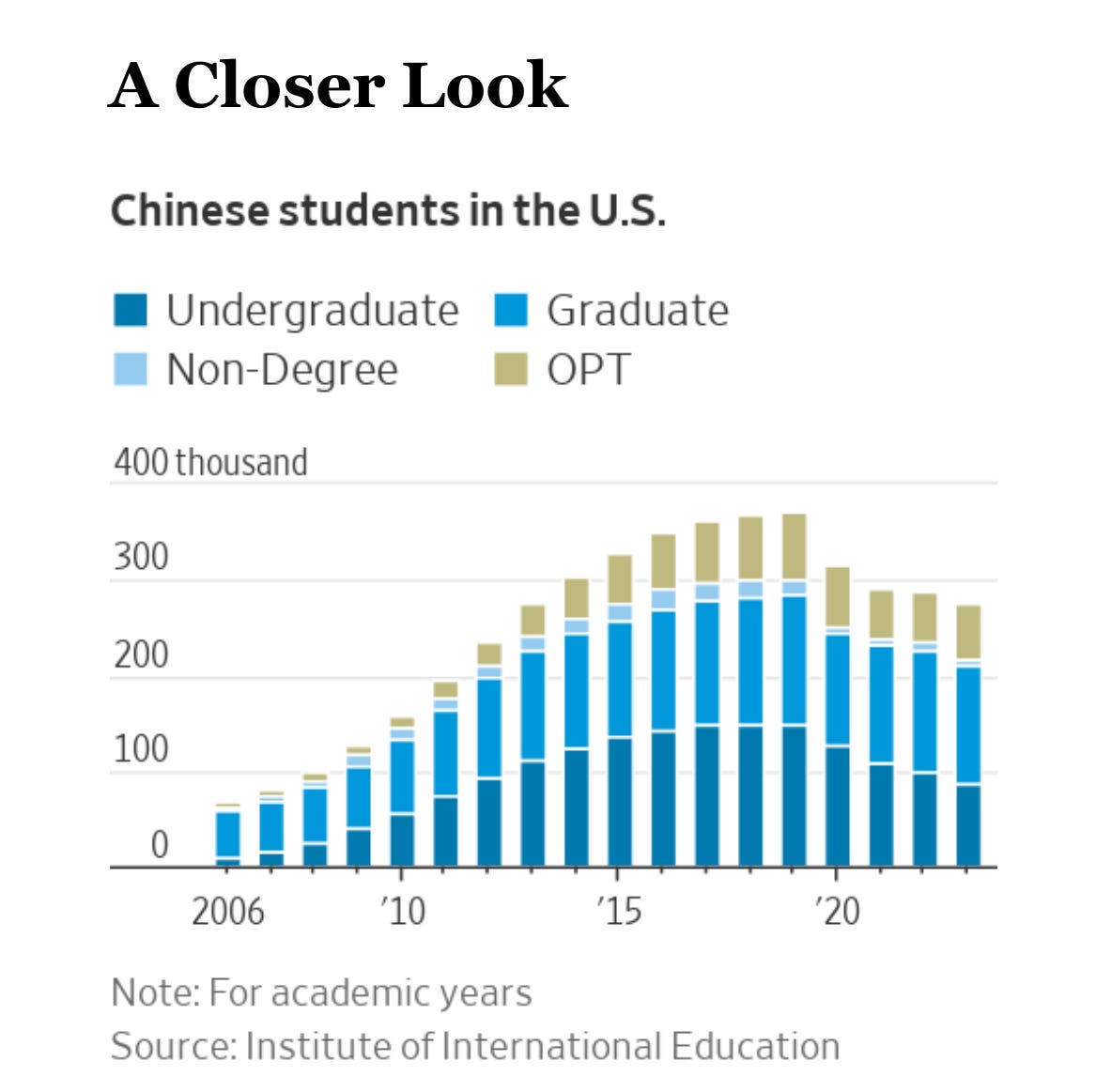

As Chinese families grow wealthier, they are increasingly motivated and financially able to send their children abroad for education, including high school. These students, who pay full tuition, are highly sought after by international educational institutions. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of Chinese students in the U.S. surpassed 300,000. While this number dipped in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and rising tensions, around 277,300 Chinese students remain in the U.S. This figure, however, is just a small fraction of the over 10 million undergraduates China produced in 2024.

Importantly, many of these students from the 1990s onward are choosing to build their lives in the U.S. instead of returning home. Their contributions are significant, especially in fields like artificial intelligence (AI), where they help sustain the U.S. dominance over China.

It is undeniable that some Chinese students may either willingly participate in or be coerced by the CCP into espionage. The U.S. government should revoke their visas and deport them. However, there is no evidence that all Chinese students engage in spying. I am concerned about calls for collective punishment against all Chinese students, which I hope do not reflect the Trump administration’s stance. Such rhetoric risks pushing innocent students with valuable skills to return to China and deterring other talented individuals from studying in the U.S. This would harm U.S. technological progress and national security, benefiting the CCP. The administration should adopt a targeted approach to address student espionage while considering the broader implications for America’s future.

Hello Helen,

Our government, and probably most governments, almost never adopts a targeted approach to solve a problem. A recent example is that our air traffic control system in far understaffed, but the rule is that air traffic controllers MUST retire at 56 years old unless they can get a specific waiver which will allow them to stay until they are 61. Their health and the needs of the system are not taken into account!!!

Same with commercial pilots on scheduled airlines that must retire at 65 regardless of health, ability, or needs of the system!!! I personally knew one private pilot who flew legally at the age of 99. He also flew at 101 years old with another pilot (legally). If he could fly at that age, he certainly could have flown a scheduled airplane far past 65; especially considering that commercial pilots (ATP) must get medical exams every six months.

Look at the COVID rules our government enforced on us! Close grade schools even though kids were unlikely to get COVID. Wear masks that did not have a chance of stopping a virus.

Getting a government to use a targeted approach to solve a problem is a dream.