The Bittersweet Memories of a Happy Dwelling --Part I

Locke's Chinese name is "樂居," meaning a "Happy Dwelling." This Chinese name can be misleading.

Chinese immigrants built the levees along the Sacramento River

Note: I recently discovered a lovely little town and its beautiful people. I want to share the town’s history and the stories of its residents by focusing on three-generation of Chinese women from one family. Since it is a long read, it was divided into two parts. Part II will appear next week. If you enjoy it, please click the “like” button, a heart-shaped symbol, or click the “share” button, a symbol with an arrow pointing up. You can find both symbols either underneath the title or at the bottom of the page in your email. Thank you!

Two things about 70-year-old Corliss Suen Lee struck me immediately when we first met. She's a petite lady with a big heart, and she couldn't stop talking about Locke, her hometown. Her love and passion for the town and her people were infectious.

Locke is a picturesque small town located in California's Delta farm region, about 25 miles from Sacramento. Established in the early 20th century, Locke is the only surviving standalone rural town in the United States built for, inhabited, and managed by Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans. Appreciating the founding and existence of Locke requires some understanding of American history.

A Brief History of Chinese Immigrants in the United States

After James Wilson Marshall discovered gold in California in 1848, Chinese immigrants joined the gold rush in California. Most were poor, unskilled young men who didn’t speak English. They wanted to find their fortune in the “Gold Mountain” (the Chinese name for San Francisco) and return to China to live like rich men.

When gold mines dried up, many went to build the transcontinental railroad, and others were hired to build levees in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta region. After the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, the railroad company laid off thousands of Chinese workers. Since many of these workers were originally farmers anyway, they joined their compatriots in building levees in the Delta region, making less than a dollar a day. They were referred to as the “wheelbarrow brigade” because they mainly used primitive hand tools.

These Chinese immigrants’ hard work turned the former swamp into 500,000 acres of the most fertile farmland in California. Besides building levees, Chinese immigrants also helped American land owners cultivate fruits and vegetables such as Asparagus and Bing cherries on the reclaimed farmland. It is fair to say without these Chinese immigrants, California would not have become the agriculture powerhouse it is today.

Orchards on the fertile farmland reclaimed by Chinese immigrants

Despite their enormous contribution to America’s economy, some Americans treated Chinese immigrants as an inferior and undesirable population and a threat to American culture and the Caucasian race. Chinese immigrants were called “Yellow Perils” and were frequently discriminated against due to their unique culture, language, living habits, dress codes, and especially their willingness to take back-breaking and often dangerous work for very little pay.

Sometimes the discrimination against Chinese immigrants became violent. On September 2, 1885, at Rock Springs, Wyoming, Rioters burned down 75 Chinese homes, murdered 28 Chinese miners, and injured a dozen more. This incident became known as the Rock Springs Massacre.

Even more outrageous was that the discrimination against Chinese immigrants was sanctioned by the U.S. government, which enacted a series of immigration laws specifically targeting Chinese immigrants. For instance, the 1875 Page Act prohibited Chinese laborers and women from immigrating to the U.S. The Page Act was based on false assumptions that all Chinese men were involuntary “coolies” (in truth, most of them came to the U.S. voluntarily) and they depressed wages for white men; that all Chinese women were prostitutes, and “caused disease and immorality among white men.”

In 1882, U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Act suspended immigration from China for ten years, with a few exemptions such as merchants, government officials, students, teachers, and visitors. Chinese immigrants were not eligible to become naturalized U.S. citizens unless they were born on U.S. soil or in China to American parents.

The Page Act and the Chinese Exclusion Act devastated Chinese immigrants, especially those who wanted to start a family. By 1910, there were only 26 Chinese wives in the Delta region. It became a custom for Chinese men to return to China to find a wife. After getting married in China, men often return to America alone to work and save more, so they would have the means to bring their wives and children to the U.S. later.

That's how Corliss's Grandmother Chow Yin Jang came to the U.S. Corliss's grandfather was born in the United States and went to China and married 22-year-old Chow in 1911. He brought his bride to the United States a year later when she was pregnant with their first child.

China had experienced a lot of turmoil due to seemingly endless wars and revolutions since the mid-19th century. Some families were eager to send their offspring abroad to find a better life. To circumvent immigration restrictions imposed by the Exclusion Act, many Chinese immigrants who already had U.S. citizenship would claim their relatives' or neighbor's children in China as their own to help these young people to America. Chinese youths who immigrated to America this way were called "paper sons" or "paper daughters." The Exclusion Act was eventually repealed by the 1943 Magnuson Act, establishing an annual quota of 105 immigration visas for Chinese immigrants.

The Founding of Locke

Despite discrimination and immigration restrictions, the Chinese immigrant population slowly grew and formed many small Chinatowns within mainstream communities. In 1915, after a fire burned down the Chinatown in Walnut Grove, a community in the Delta region, some Chinese residents decided to move up the Sacramento River. Since California's 1913 Alien Land Act prohibited the Chinese from owning land, these Chinese leased about 10 acres of land from a local farmer named George Locke. They built a detached Chinese town and named it "Locke" to honor their landlord.

During Locke's heyday (between 1920 and the mid-1950s), it had about 600 permanent Chinese residents. Thousands of Chinese farm workers would flock to Locke to find food, lodging, and entertainment during planting and harvesting seasons.

On the town's Main Street, the only business run by white Americans were four whorehouses. The Chinese owned and ran everything else, including a boarding house, several gambling houses, grocery stores, restaurants, and slaughter houses. Americans from Sacramento and San Francisco travelled to Locke to seek speakeasies frowned upon elsewhere. Locke was lively, fun, and full of noises and commotions.

The front of a gambling house in downtown Locke. It’s a museum today.

But at one end of Main Street, there was a Chinese school funded by generous contributions from residents and businesses including the gambling houses. Children of Chinese farmers and business owners learned Confucian virtues such as propriety and righteousness. In Locke, vice and virtue strangely and peacefully coexisted.

Grandmother Chow Yin Jang

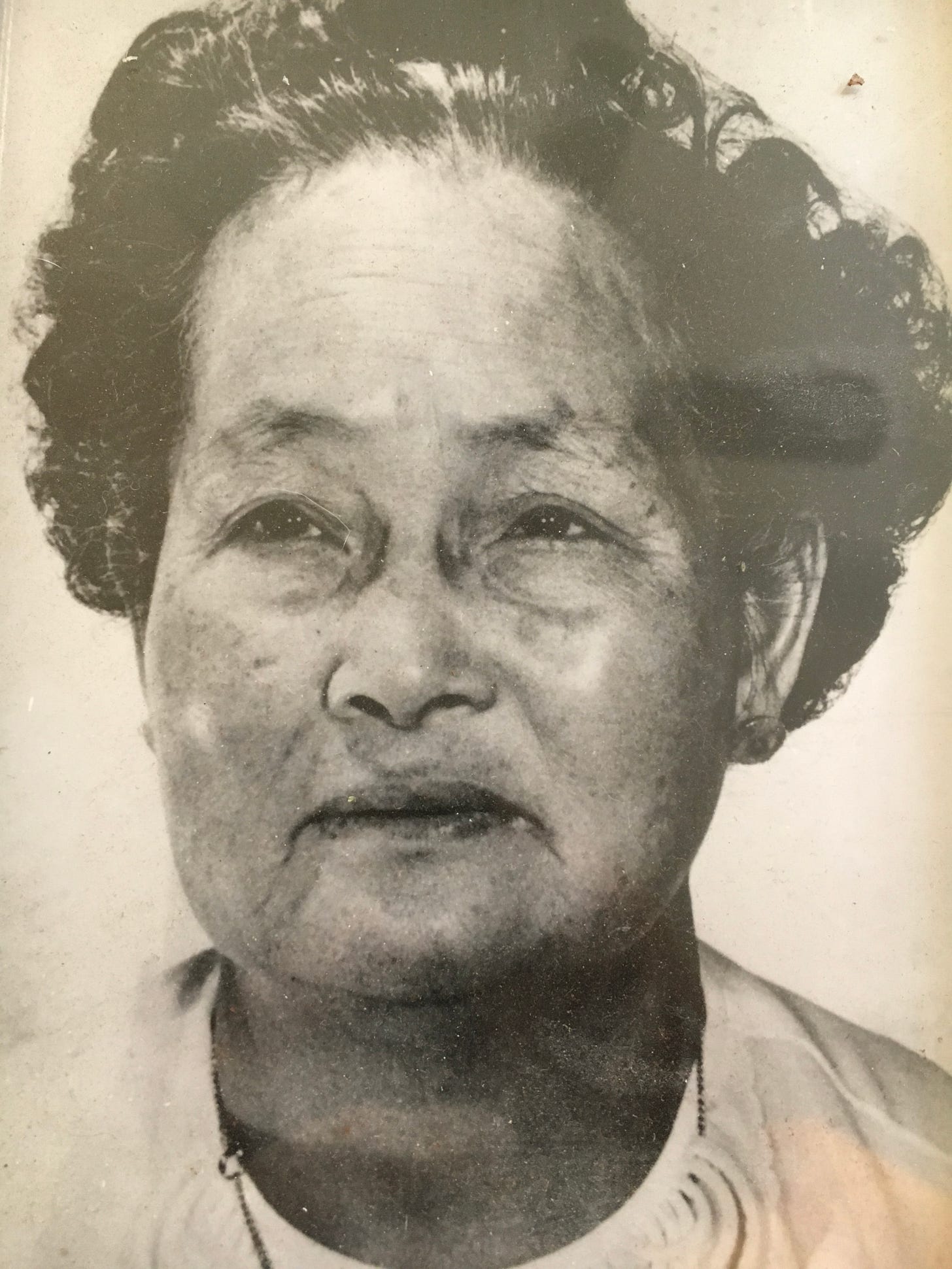

Photo of Grandma Chow, courtesy of Corliss Lee

Locke's Chinese name is "樂居," meaning a "Happy Dwelling." This Chinese name can be misleading because early Chinese residents, especially women, had endured tremendous hardship and had to overcome all sorts of challenges by working extremely hard.

Take Corliss's Grandmother Chow Yin Jang as an example. Chow was 23-years-old when her husband brought her to the United States, and they were among the earliest residents in Locke. They had 12 children, 10 of whom were born in eleven years.

A typical day for grandma Chow began with cooking breakfast for her husband and the children, cleaning the house, and watering her vegetable garden. Many Chinese households in town had a vegetable garden, which provided fresh vegetables for their family and helped save money on groceries. Grandma Chow grew various vegetables, including potatoes, bitter melon, and snow peas. Whenever she had a good harvest, she shared her produce with neighbors and friends.

During the day, grandma Chow would let her older children look after the younger ones when she worked in the packing shed packing pears. On her way to work, she always brought extra food to feed all the cats in town. After getting off work, grandma Chow went home and did more cooking, cleaning, and laundry. Her way of living was representative of most Chinese women in Locke and, by extension, in the Delta region. They worked from sun rise to sun down and barely had any break.

Corliss said grandma Chow was an excellent cook, and some of Corliss's favorite food her grandma cooked included deep-fried Sesame balls and Dim Sum Bao. One of Corliss's fond memories of Locke was every day when she was walking home after school, the fragrant aroma of deep-fry, boiling soup, and stir fry from grandma Chow and other Locke women's cooking permeated the Main Street. She still remembers that smell today.

Grandma Chow worked all her life tirelessly. Even after all her children grew up, grandma Chow continued to work in the packing shed, sometimes alongside her granddaughter. Grandma Chow didn't retire until she was almost 70-years-old. She passed away in 1982 at age 93. Corliss said she learned the importance of dedication, determination, and kindness from her grandma.

Since her family moved to Locke in 1915, Grandma Chow never left the town because it was the only place she felt safe. The fact that Locke was built and managed by the Chinese and the town's secluded location provided a sanctuary for Chinese immigrants like her. They were mostly sheltered from discrimination, bullying, hostility, and violence that their compatriots had to endure in the rest of the country from the 19th to the mid-20th century. In Locke, Chinese immigrants like grandma Chow were able to raise their families and build their lives in relative peace. For them, Locke was a "Happy Dwelling" despite the hardship.

To be continued next week…

If you like to know more about the immigration history in the United States, please check out my book on Amazon.com, “The Broken Welcome Mat: America's UnAmerican Immigration Policy and How We Should Fix It.”